The Dragons

by Theodora Goss

One day, the dragons came.

It was on a Tuesday, she remembers. It was

the sort of thing that would happen on a Tuesday,

which is an unsatisfying sort of day,

not the beginning of the week, nor the middle,

without the anticipation of a Thursday.

A troublesome sort of day.

And there they were, sitting on the back porch railing,

where she had hung boxes for geraniums

that summer. But now, since it was November,

there were no geraniums — only dragons, quite small,

the size of a Pomeranian or Toy Poodle,

but of course with scales, which shone with a dim sheen

in the gray light of a rainy Tuesday morning.

Seven of them — green, blue, red, orange, another orange,

a sort of purple, and a white one that seemed smaller

than the others, the runt of the litter. It shone opalescent.

They were damp with rain, and obviously

too young to be out on their own. Had someone abandoned them,

the way people sometimes leave dogs at the edge of the woods?

Or were they feral, born to a wild mother?

She couldn’t just leave them there. As soon as they saw her,

the white one started a piteous baby roaring

and the green one joined in, showing the interior

of its pink mouth, like a geranium with teeth.

But when she opened the porch door, they just sat there,

staring at her with iridescent eyes.

What did dragons eat? She had no idea,

so she put half of last night’s Chinese takeout

in a bowl outside the porch door.

The rest she put into another bowl, inside

the open door, then went to get ready for work.

By the time she returned, in her suit and sensible pumps,

they were curled up on the sofa, already asleep,

except for the blue one, which hissed at her, not in anger,

she thought, but simply to let her know it was there.

The bowls were empty.

They continued to be trouble.

The orange one burned a hole in the carpet, or was it

the other orange one? They were so similar,

initially she could not tell them apart.

But eventually she learned to distinguish them

by their quirks and personalities —

one was just playful, the other more mischievous.

She gave them all names: Hyacinth (that was the purple),

Orlando, Alexander (after her brother,

who was a software designer in San Francisco

and sent her pictures at Christmas of his apartment

decorated with plastic poinsettia).

Ruby (a little too obvious, but it suited her),

Dolores and Delilah (the orange ones),

and little Cordelia, the runt, who affectionately

clawed apart her favorite afghan

while trying to climb the armchair into her lap.

She tried calling the ASPCA

and the local veterinary clinics, but no one was missing

a clutch of dragons. The receptionist at one clinic

thought she meant geckos.

What in the world was she supposed to do with them?

The nearest shelter said it had no facilities

for dragons, sounding a little incredulous

over the phone. Meanwhile, they scratched the furniture,

got tangled in the hangers while creating

a nest in her closet of scarves and pantyhose.

She could not leave out a pair of earrings, or coins

in a jar for laundry and parking — anything shiny.

They would begin to hoard it, hissing at her

when she approached to take back her watch or car keys.

Her bills for Chinese takeout

were astronomical.

She took sick leave when Orlando and Alexander

both caught pneumonia and had to be nursed back to health.

(She finally found a vet who would treat dragons,

a younger guy trying to establish a practice.)

“I’m not sure about dosage,” he said, as he gave her

a prescription for antibiotics. “About the same

as for a golden retriever? But it’s just a guess.

Aren’t they getting a little big, for a place

of this size?” And she had to admit he was right.

Now when Ruby curled up next to her

as she watched Casablanca, the red dragon

took up half the sofa. Her sort-of-boyfriend,

Paul, who worked in the tax and bankruptcy group,

started complaining. She understood his perspective —

the dragons had never liked him. Hyacinth

always bellowed when he came over, Delilah

peed on his baseball cap, and Dolores chewed

a corner of his briefcase. “They’re dragons,” he told her.

“They’re dangerous — what if they bite someone? You’d have

a lawsuit on your hands. I really don’t know

why you keep them around.”

Probably because they were warm at night,

piled on her bed, with Cordelia’s silky muzzle

tucked under her chin. Whenever she got home

after a long day at the office, they greeted her,

trilling in unison. They never told her

that her hairstyle didn’t fit the shape of her face,

or she really should lose a few pounds, unlike her mother.

They never asked her to file incorporation

documents yesterday, or talked to her

for an hour about baseball while she was trying to listen

to NPR. Anyway, who would take them,

all seven of them? Dragons don’t make good pets,

and she hated the thought of separating them.

They needed each other.

Finally, she moved to a lighthouse in New England.

She saw the advertisement — Lighthouse keeper

wanted. Must be willing to live on an island

off the coast of Maine, near Portland. Competitive salary.

The ferry comes twice a week. She can take it to Portland

if she wants to, but it brings everything she needs,

from lightbulbs to chocolate chip cookies to art supplies.

Sometimes she goes, just to get Chinese takeout.

The dragons have learned to fish and fend for themselves.

She watches them flying up in the sky like kites

when she goes on her morning walk, collecting shells

and bits of seaglass. Mostly they stay outdoors,

but Cordelia still sleeps in the bed beside her at night,

stretched out on the blanket. She has not grown much larger

than a Great Dane, although Alexander is now

the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. On sunny mornings

she finds them lying on the rocky shore, like seals,

shining in the sunlight. On rainy days, there’s a cave

on the other side of the island, although Dolores

curls up in the lighthouse itself, around the beacon.

On stormy nights, she’s seen them guide a ship

to shore, which seems an unusual behavior, but dolphins

do it, so why not dragons?

She’s started painting again, the way she used to

when she was a teenager, before her father

told her to focus on something more practical.

Her canvases sell in a gallery and on her website.

Mostly, she paints the dragons — rolling around

in the waves, lying on the shore, cavorting above

in intricate arabesques, as if they knew

she was sketching below, showing off for her.

She doesn’t make as much money

as she did at the law firm. But then, on the other hand,

she has dragons.

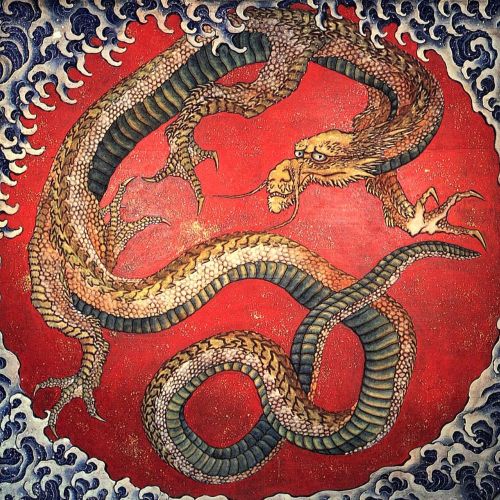

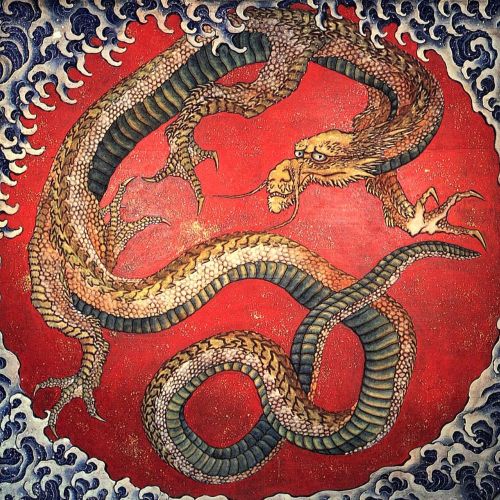

(The image is a painting of a dragon by Hokusai.)