The Witch Makes Her To-Do List

by Theodora Goss

Check on the frogs

in the pond, especially the one

with the crooked leg, who can’t hop as far

as the others. Ask them

how they are doing, whether the dragonflies

are plentiful this year, if any of them

have turned into princes lately.

They always croak at that, which is their way

of laughing.

Bring in the laundry — the cotton sheets

a resident ghost likes to play in, the pillowcases

scented with lavender

that will ensure only good dreams,

your black turtleneck and faded blue jeans,

your peasant blouses and a tiered skirt

the color of autumn leaves,

crimson and yellow and brown,

suitable for an afternoon in town

doing research at the public library or meeting

customers for your custom face creams

and love potions (the most popular

makes any woman fall in love

with herself — tricky to mix, that).

Try to find your crocheted hat, which must be

where you left it, but somehow isn’t.

Count the socks. If any have gone missing,

speak to them sternly. Really,

they’re supposed to keep track of each other!

Yet they never do.

Sweep the house. Sweep out

the old energy, which has gone dull

and stale. Sweep in the cold, clear air

of autumn. Sweep in time

to do the things you need to before winter

comes. Sweep in joy, and a fresh start

to the new week. While you are at it,

sweep out your heart

and open its windows for a while.

Gather herbs from the garden —

hyssop, fennel, rue. Tell the rabbits

they will rue the day they ate all the carrot tops.

Laugh at your own joke, share it

with the spider sitting at the center of her web

between the fenceposts. She will stare at you

with her black eyes, all eight of them — tough audience.

Check and make sure that damn cat

isn’t bothering the birds. “No flying on the broomstick

if I find feathers!” you’ve told her.

You’re pretty sure she’s been chewing the corners

of your magical books, and also the Agatha Christies

in revenge, but she insists it’s moths.

Make the teas and tinctures:

comfrey, yarrow, valerian. Bottle them

in small glass bottles, stopper them with wax,

label them in a neat, sloping hand,

the way you were taught to write in primary school

by a very strict Mrs. Johnson.

Sprinkle sage over the wooden floor

to keep away the mice. They’re so annoying,

waking you up at night with their endless chatter.

Afterward, clean the kitchen.

Dust the jars labeled Midsummer Morning Dew,

Maiden’s Sweat, Unicorn Urine, Water

From a Well That Has Always Been in Shadow,

Tears (mixed), Fears (assorted),

Rose Petal Essence (not from concentrate).

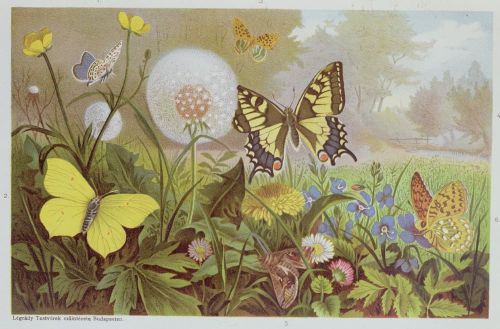

Remember to dust the tray of butterfly wings,

the stack of bones you gathered in the forest,

the bowl of random keys, including piano.

Feed the coyote skeleton you found one summer.

He can’t really eat, poor thing,

but he likes to pretend. With a jewelry cloth, polish

the moonstone globe that reflects various phases

of the moon and foretells the future — as long

as it’s not too distant, but sometimes

it’s just as useful to know what will happen soon.

When you’re done, make a mug of ginger tea

and rest for a while.

Bicycle into town

wearing the tiered skirt, a warm coat,

a scarf that flies out behind you. Along the way,

shout “Hello!” to the chestnut and linden trees.

They will wave their leaves back at you, saying

sleepily, Sister, we hope you’re well.

Say a spell under your breath for their continued

good health, for no worms or blight,

for quiet nights under the snow so when the sun

returns, when warmth comes again, they will awaken

renewed. Because after all, winter

is better than any face cream

for smoothing out the wrinkles of the world.

Stop at the library for that book on summoning

the Spirit of Inspiration or a volume of Mary Oliver,

whichever works better, the grocery store

for peppermint chip ice cream

and tuna for that damn cat,

because after all she’s your damn cat, your Serafina,

who curls up next to you on autumn evenings,

warmer than a hot water bottle,

who remembers the words to spells

as well as classic rock ballads

when you seem to have forgotten them,

and can always find your mislaid reading glasses.

Maybe you’ll take her flying after all,

then watch Murder She Wrote on television.

Drop off a jar of ointment for old Miss Bridges,

who has rheumatism and trusts you more

than her doctor, although you remind her to take

her heart medication. “It’s not a competition,”

you tell her. On your way back,

stop to gossip with the squirrels, who always seem

to know what’s going on, those furry rascals,

rats with extravagant tails, but really quite clever.

Make dinner. Play scrabble with Serafina

and the ghost, who knows seventeenth-century words

you have to look up in an ancient dictionary.

It looks like rain, so make plans for flying tomorrow

to gather water vapor from the clouds

hanging around the mountains —

your Unfallen Rain bottle is getting low,

and it’s such a useful ingredient for minor curses.

Before you go to sleep,

check on the bats

in the attic. Are they comfortable,

hanging together, their furred bodies

next to each other, upside down

like a row of inverted coats,

their delicate ears

quivering? What have they heard

from the universe lately?

What’s the news?

(The image is The Witch’s Daughter by Carl Larsson.)